This page of the tax equity analysis addresses issues associated with the tax code that may limit the amount of the tax benefits. I discuss issues like the DRO (deficit restoration obligation), the outside capital account, suspended losses, 734 depreciation adjustments, qualified income offset, hypothetical liquidation at book value, 704(b) inside capital account, minimum gain and deemed losses. I attempt to present focused examples that demonstrate the mechanics of how the tax rules work and how the tax constraints affect the ultimate cash flow and IRR of partners. (I couldn’t give a crap about exactly why these arcane rules occur — I just want to model them correctly). I label these things potential tax constraints and the effect of these on taxes “stranded tax”. When attempting to understand these tax constraints I have been very frustrated by the arcane language, the lengthy excel formulas, the limited full explanation of how different rules affect partner value and differences in tax accounting assumed in different presentations. To work through this horrible stuff, I have tried three things. First, I have tried to read through articles and slides prepared by lawyers (this can be torture and you have to be in a special mood to make it through them). Second, I have tried to work through detailed models created by other people that I have been able to collect and then I have tried to replicate the details of different formulas. Third, I have tried to create focused examples which eliminate a lot of the junk that illustrate exactly how these things can affect cash flow and IRR without liquidation of the partnership. On this page I focus on the third method and provide some focused examples. For me, the ultimate question of all of this stuff is the risk for a tax equity partner that will ultimately result in not being available to use the tax benefits. expensive lawyers seem to love to confuse.

In the discussion below I refer to various articles that explain the various tax rules and the constraints. I have put the articles in the resource library. If you want access to the library send me an e-mail at edwardbodmer@gmail.com. Unfortunately, the articles can be difficult to read and confusing. Virtually all of the articles start with very basic ideas about why a tax investor is necessary and the creation of a partnership (I get sick of this stuff). Then they are sometimes so detailed and arcane with tax acronyms and references to the tax code that they are practically impossible to decipher. Other times they make vague references to the DRO as if the DRO was some kind of cash account and drives the economics of a transaction (which it does not). I need to make a gigantic disclaimer here. I am not a tax accountant; I am not a tax lawyer; I have never charged high fees for consulting on this stuff (If you call me I will be happy to walk through my understanding of the issues with a modest fee in the hundreds of dollars), and I have not been a financial advisor. So if I have some details about the specifics of the minimum gain charge back account in the 704(b) capital account and its effect on the use of the DRO which may affect income re-allocation, please do not sue me.

Capital and/or Basis Accounts — What Are They and What Matters for Cash Flow and IRR

Tax equity models often include six capital accounts — two capital accounts for the tax investor, two for the sponsor (I sometimes call the sponsor the developer, sorry for the confusion), and two for the overall partnership. Balances in these capital accounts drive many of the potential tax constraints like suspended loss and the deficit restoration obligation. Therefore, the first section of this page addresses various issues associated with the inside capital account and the outside capital account. The first issue to address is what exactly is a capital account. The second issue is what is the fundamental difference between the outside and inside capital account (in contrast to less important details between the outside basis and the non outside basis). The third issue is which account really matters in terms of cash flow to the tax investor and the sponsor. Before starting, you should become familiar with some terms for capital accounts:

- Inside Basis is 704(b) or book basis

- Outside basis is tax basis

Each partner in a partnership flip transaction must track its “capital account” and “outside basis.”These are different ways of measuring what each partner invested and took out of the deal. If either measure goes negative, then it is a sign that the partner took out more than his fair share. They are

also a limit on the capacity of the investor to absorb tax benefits. Consequently, it is important to model both accurately.” Note that this contracts another presentation and models that state the capital account or inside basis or 704(b) account can have a negative closing balance, but the outside basis cannot be negative.

Video on Summary of Tax Investor IRR and ROI

How disgusting is this. To compute the ROI which is the MIRR with a zero re-investment rate when the ITC is received almost immediately and the true investment is just the excess above the ITC. Further, all they did is give you a hard copy without seeing how the model works. But Harvard students are taught how these very complex transactions are very creative. It makes me want to throw up.

Issue 1: A capital account (inside or outside) is just like any equity account when there is no debt. With debt at the partnership SPV, the outside basis is the allocation of the net assets.

Let’s address the first issue. A capital account is just like any equity account that includes paid in capital and retained earnings. Both the inside capital account and the outside capital accounts are essentially equity accounts if there is no debt at the partnership level. Like any equity account, you can start with an opening balance, add net income, add capital contributions and deduct dividends. Both the outside and the inside capital increase via capital contributions and (positive) income allocations. Both decrease via cash distributions and losses (negative income) allocated.

If there is no debt for the partnership, the sum of capital accounts should be the same as the tax basis. If you think of a really simple case with no current assets and no cash and no debt, then the total assets are the net plant. As the balance balances, the net plant equals the total equity. Therefore in a simple case, the capital account is the same as the net plant of the project or the tax basis.

Sometimes the inside capital account is vaguely thought of a book basis and the outside capital account is though of as a tax equity account. One article I read referred to the inside basis as “inside basis / book basis – fair market value (FMV).” The outside basis was referred to as “Tax basis / outside basis – cost basis.” For either the inside capital account or the outside capital account the depreciation expense is measured at the tax depreciation rates when computing income and not something like a straight line rate that may be used in financial accounts. This is illustrated by one of the legal presentations I read stated that “book depreciation each year will bear the same ratio to the book basis as the tax depreciation each year bears to the tax basis.” This confusing language just means that you use tax depreciation rates.

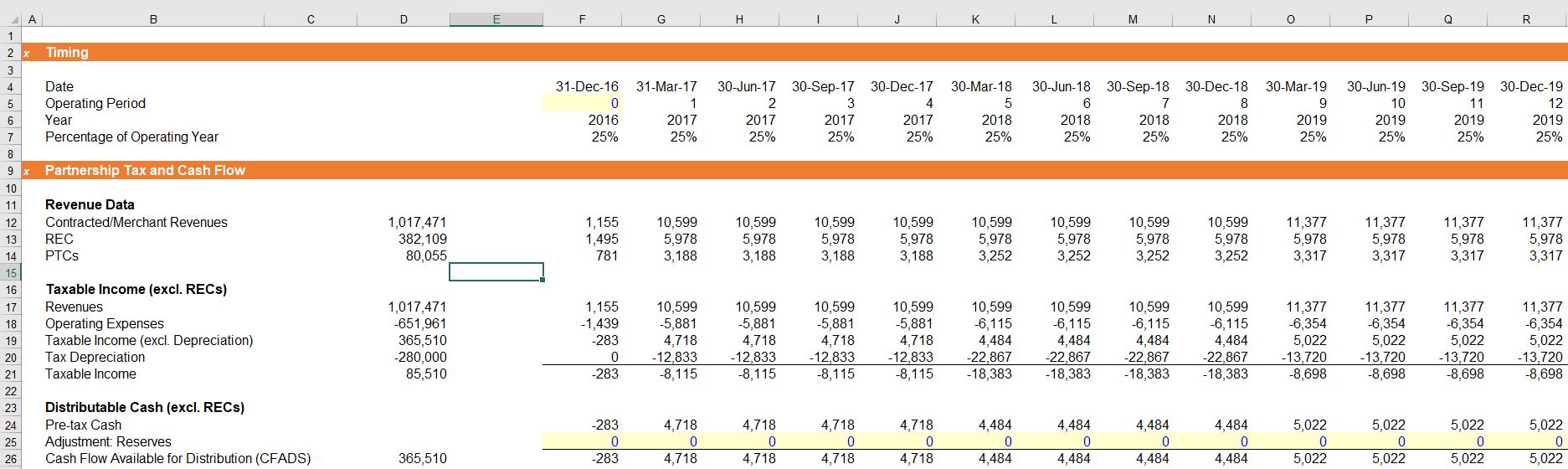

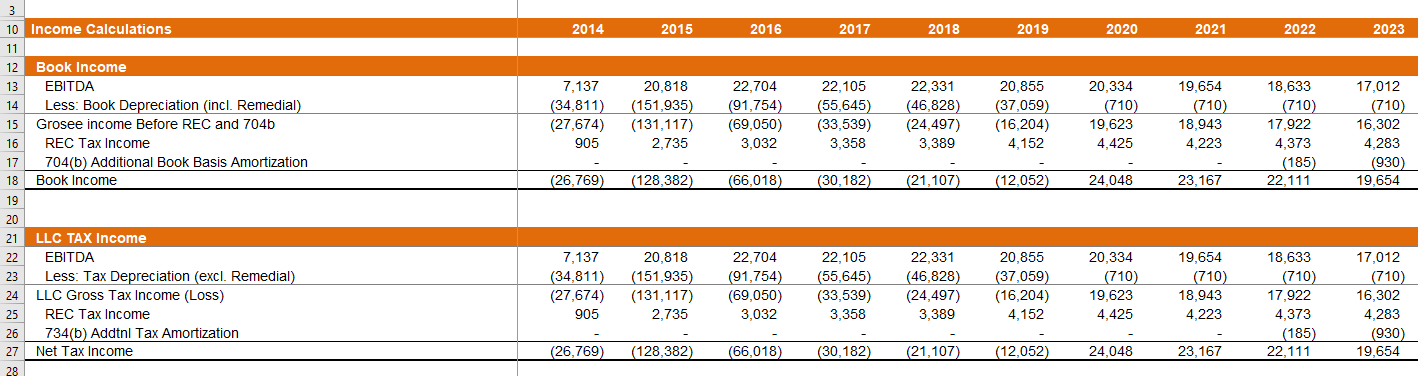

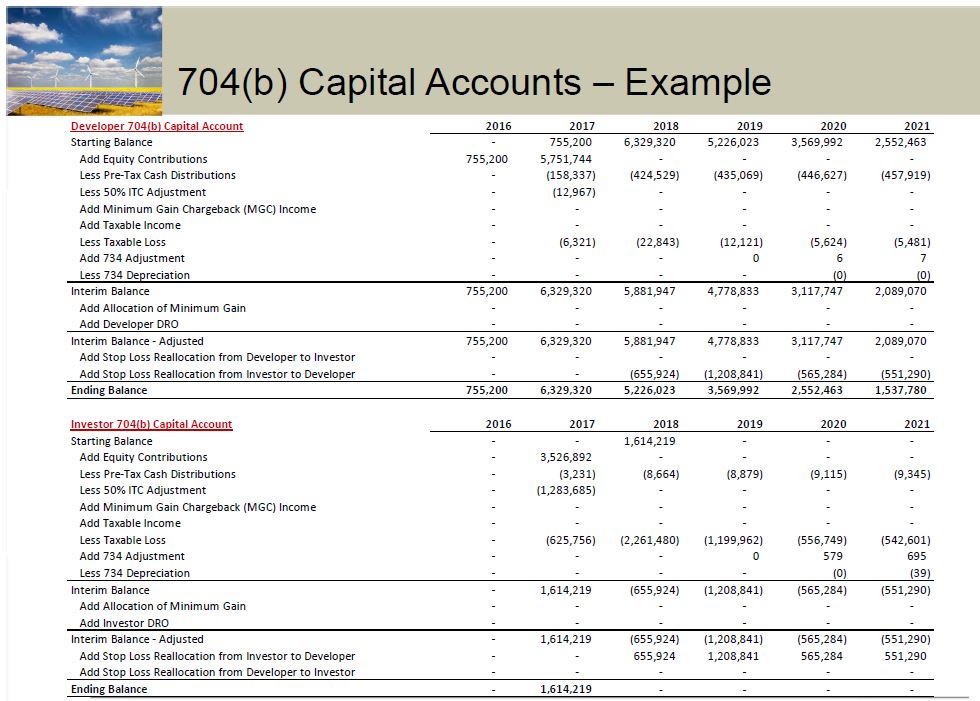

To illustrate how the capital accounts work I have put a couple of examples below from different sources. Note that in the screenshot below the book income is the same as the income for income tax purposes. The only difference is that in the book income calculation the depreciation can include remedial depreciation. Further, it is possible that an account named 704(b) additional book basis amortization may be included. In the case of the tax income, the remedial depreciation is not included but something called 734(b) additional tax depreciation is included. For purposes of understanding the fundamentals of the inside capital account or the book capital account versus the outside capital account, these added depreciation amounts are not included in the first examples meaning we just need one income calculation. I am trying not to muck up thing with all of these horrible accounts and focus on how the constraints can affect the IRR to investors.

Partnership Allocation

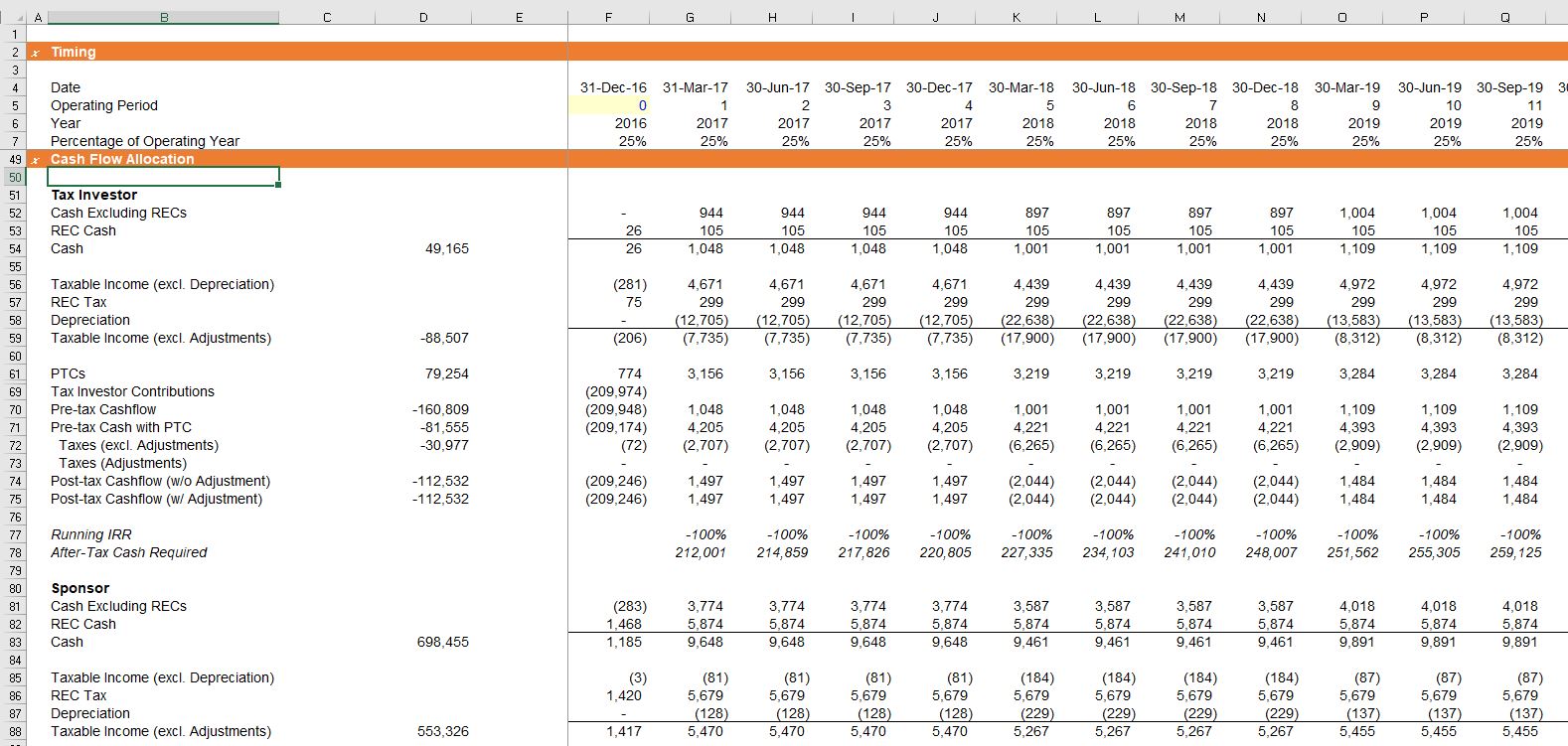

Cash Flow Allocation

Issue 2: What is the fundamental difference between the different capital accounts

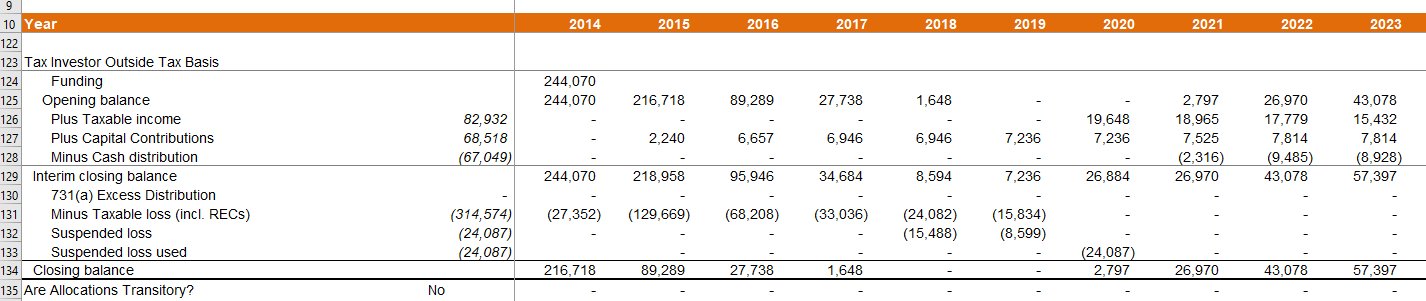

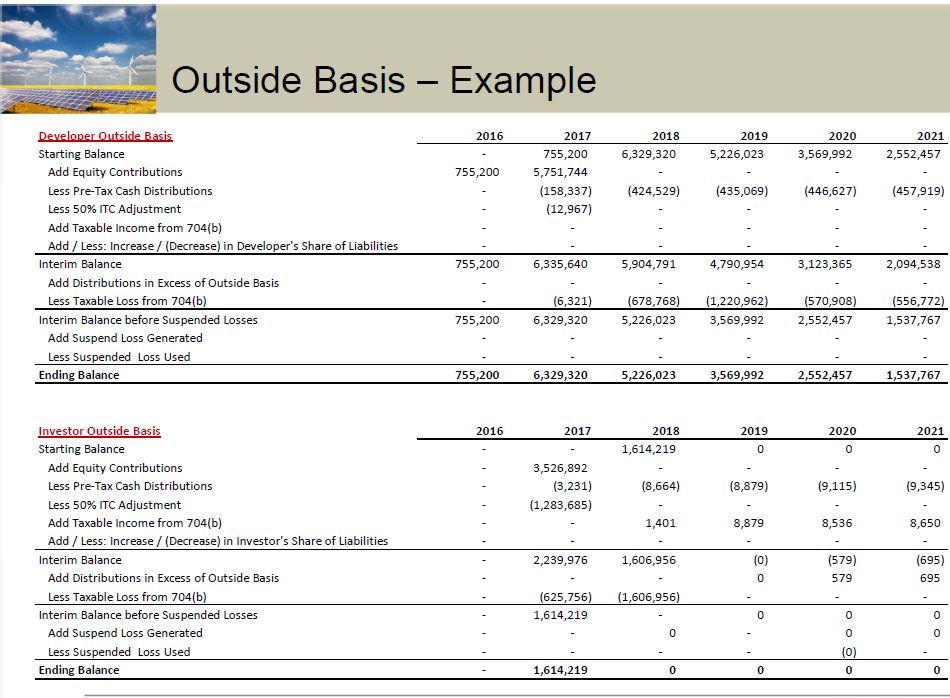

I have included a couple of screenshots that illustrate the two capital accounts (inside and outside) below these paragraphs. When you look at the screenshots below, you can see different titles in the accounts. The main difference in the capital accounts is that outside capital account that may be called the tax basis cannot fall to a negative amount. If there was one investor (and no debt) or if both investors had the same ratio of income to equity investment (e.g. if both investors put in 50% and they both get 50% of the income and dividends) then the account could not be negative. This is just because the balance sheet must balance. On the asset side, the net assets are positive as long as there are not big write-offs or negative residual value. This means that if the only account on the liabilities and capital side is equity, the equity cannot be negative. The way a capital account can be negative is if the tax investor takes more of the losses relative to the amount of his investment.

One of the articles I read suggested that “most tax equity investors run out of the capital account before they are able to absorb 99% of the depreciation.” In the screenshots below, the first illustrates an inside or book basis for the capital account (it is titled Income Calculations). The second screenshot illustrates the outside capital account or the tax basis. Note that the accounts are the same until the fourth year. As shown in the second screenshot below, the outside basis has a potential adjustment at the end for stop losses and cannot be negative. In these accounts, the cash distribution includes only the pre-tax income. Note that the suspended loss is like an NOL account.

- Think of 704(b) capital accounts (inside basis) and outside basis as “tax accounting statements” – every partnership has them.

- 704(b) capital account (inside basis) starts at the sum of the cash and property (at FMV) that the partner contributes to the partnership. Generally this is the same as the book basis — the cost.

- In Both 704(b) capital account (inside basis) and outside basis go up (by taxable income allocated to the partner) and down (by cash distributed or taxable losses allocated to the partner) during the life of the partnership.

- In 704(b) capital account (inside basis) is its claim on partnership assets at liquidation.

- Outside basis will determine how much taxable gain a partner has if it sells its partnership interest.

- Both 704(b) capital account (inside basis) and outside basis restrict the amount of taxable losses that the partnership may allocate to a partner to the equity that the partner has contributed to the partnership. Typically, ending balances cannot go below zero.

- Outside basis starts with the sum of the cash and basis of property (generally, at cost) that the partner contributes to the partnership. (If the partnership has non-recourse debt, then the partner’s share of this debt is added to its outside basis).

Issue 3: Which of the capital accounts really matter

Maybe I have no business saying this as I have not seen this point in the articles (that you can get by sending me an e-mail at edwardbodmer@gmail.com), but the suspended loss and the outside tax basis is a lot more important than the book basis and all of the painful discussion about deficit reduction obligations. In a time-based flip the suspended losses will directly affect the tax investor IRR. With a yield-based flip, the developer/sponsor IRR is more affected as the time to the flip is extended. In contrast, Losses allocated to a partner are only allowed to the extent of the partner’s “outside” tax basis in its partnership interest. Excess losses are suspended and carried forward until the partner has sufficient tax basis.

But this does not work with the outside capital account goes negative. If the outside capital account is negative, there are cash flow effects on the tax investor because tax depreciation is transferred from the tax investor to the sponsor.

- Account behavior – what happens if cap account or tax basis goes negative?

- Cap Account: one or both partner cap accounts allowed to go negative

- Negative cap account does not automatically result in a Deficit Restoration Obligation (“DRO”)

- DRO results when one partner’s capital account is negative while the other partner’s capital account is positive (or, if debt, one partner’s capital account is disproportionately negative)

- Tax basis or the outside is NEVER allowed to go negative

- Suspended losses – correction for when tax losses would drive tax basis negative

- Excess distributions – adjustment for when cash distributions would push tax basis negative

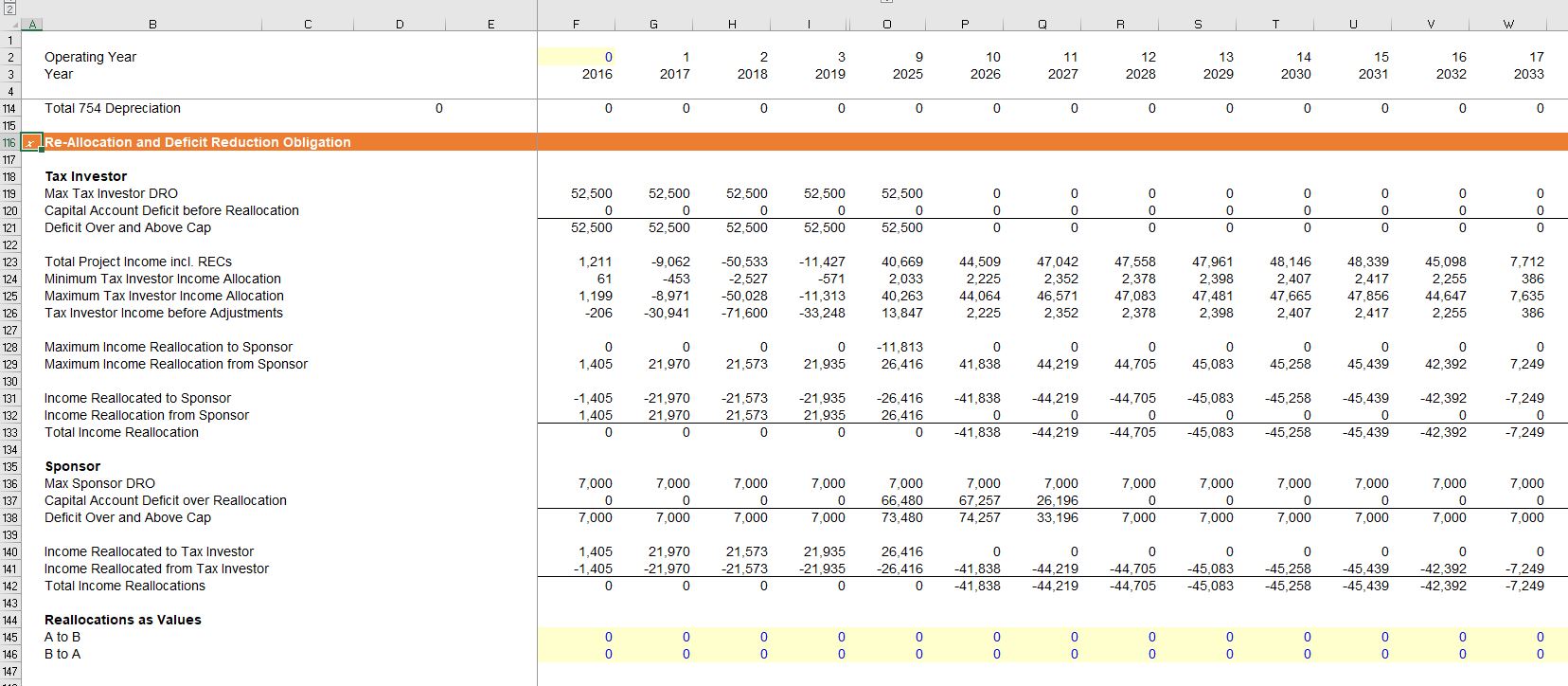

Loss reallocation (stop losses)

- Maintains a partner’s capital account balance at zero or prevents it from becoming disproportionately negative (i.e. prevents DRO)

- Inefficiencies for PTC deals

- In the early years of a project, stop losses steer taxable loss away from tax equity investor

- Provides sponsor with taxable losses it may not be able to utilize

- PTCs also transferred to sponsor in same ratio as the final income allocation!

- Suspended losses still count as an income allocation for overall income allocation percentage and subsequent PTC allocations

Does the Deficit Restoration Obligation Only Matter at Liquidation and Only Apply to One of the Capital Accounts

The DRO applies to the capital account (the inside capital account) and not the outside the capital account. One way to deal with the problem for the inside capital account (not the outside capital account) is for the tax equity investor (not the sponsor) to make a capital contribution to the partnership when it liquidates. This contribution is the DRO. Note that the contribution does not occur until the tax investor exits the investment.

This is the kind of confusing language that you get “In lieu of a qualified income offset, a partner with a negative capital account (this would be the tax investor) may sign up for a DRO so that losses continue to be allocated to the partner even though its capital account is negative.” What in the hell does this mean to people like me.

- Allows tax losses or cash distributions to drive a partner’s cap account below zero instead of reallocating income

- The tax investor essentially “borrows” equity from the sponsor to claim tax loss or tax free cash distributions

- Requires the partner taking the DRO to contribute capital in the event of a liquidation

- Unlikely scenario but real credit risk nonetheless

- Relative risk profile of DROs created by tax losses as opposed to cash distributions

How does the DRO work during the liquidation period.

- DRO – Deficit Restoration Obligation (“Impermissible Negative”)

- Allows tax losses or cash distributions to drive a partner’s cap account below zero instead of reallocating income

- One partner essentially “borrows” equity from the other to claim tax loss or tax free cash distributions

- Requires the partner taking the DRO to contribute capital in the event of a liquidation

- Unlikely scenario but real credit risk nonetheless

- Relative risk profile of DROs created by tax losses as opposed to cash distributions

If capital that is computed using the pre-tax income (less depreciation deductions) and the non-tax related dividends falls to zero, a partner is not allowed to continue receiving tax benefits. It is not surprising that the partner that is exposed to limits on tax is the tax equity investor. To compute the potential exposure, two different capital accounts can be be set-up and something called deficit reduction obligations may be used.

A partner’s capital account is the partner contributions, increased or decreased by the partner’s share of income or loss and decreased by partner distributions. For this purpose, income and loss refers to the book definitions.

If the partnership liquidates in accordance with capital accounts, the book allocations drive the economics of the deal.

Taxes paid by the partnership on behalf of a partner are typically treated as a deemed distribution.

The agreement likely intends to follow the safe harbors if, after paying creditors and setting up reserves, the agreement distributes the remaining proceeds according to the partners’ §704(b) capital accounts.

In lieu of a qualified income offset, a partner with a negative capital account may sign up for a DRO

(typically a limited DRO) so that losses continue to be allocated to the partner even though its capital

account is negative

Does Qualified Income Offset Affect Cash Flow to the Tax Equity Investor

If the capital account of any partner is negative after the initial allocations of cash and taxable

income/losses, there may be a reallocation of income between partners, referred to as a

“qualified income offset” or “QIO” in an amount necessary to eliminate any negative capital

account balances.

Excess Distributions

(a.k.a Distributions in Excess of Tax Basis a.k.a 731(a) Excess Distributions)

- Results when cash distributions (before tax losses) pushes a partner’s tax basis below zero

- Deemed to be a sale of part of the interest and requires partner to recognize a gain

- Cash distributions to a partner are tax free to the extent they do not exceed the partner’s tax basis

- Wind Energy models assume capital gains taxes of 20% for distributions to Wind Energy

- C-corp excess distributions are taxed atDifference between suspend loss, excess distributions and stop loss reallocation. Tax basis is not allowed to become negative•Suspended losses –correction for when tax losses would drive tax basis negative

•Excess distributions –adjustment for when cash distributions would push tax basis negativeLoss reallocation (stop losses)

•Maintains a partner’s capital account balance at zero or prevents it from becoming disproportionately negative (i.e. prevents DRO)The allocation of tax is shown in the screenshot below.

Post-target flip allocations

Tax equity will often want higher allocations of cash in the event they don’t reach their target flip IRR on time. This can cause some serious concerns for backleverage and cash equity investors.

- Capital account & tax basis impacts of excess distributions

- Tax basis – a gain (income) is recognized which brings tax basis back to zero

- Cap account – excess distribution gives rise to an intangible asset that increases the capital accounts (ignoring built-in gain / deemed value)

- Sharing of new asset between partners subject to negotiation

- New intangible asset is depreciated via 15 year SL

- Depreciation deductions from these new assets can be specially allocated (some ambiguity to this provision, safer to allocate in same ratios as gross income)

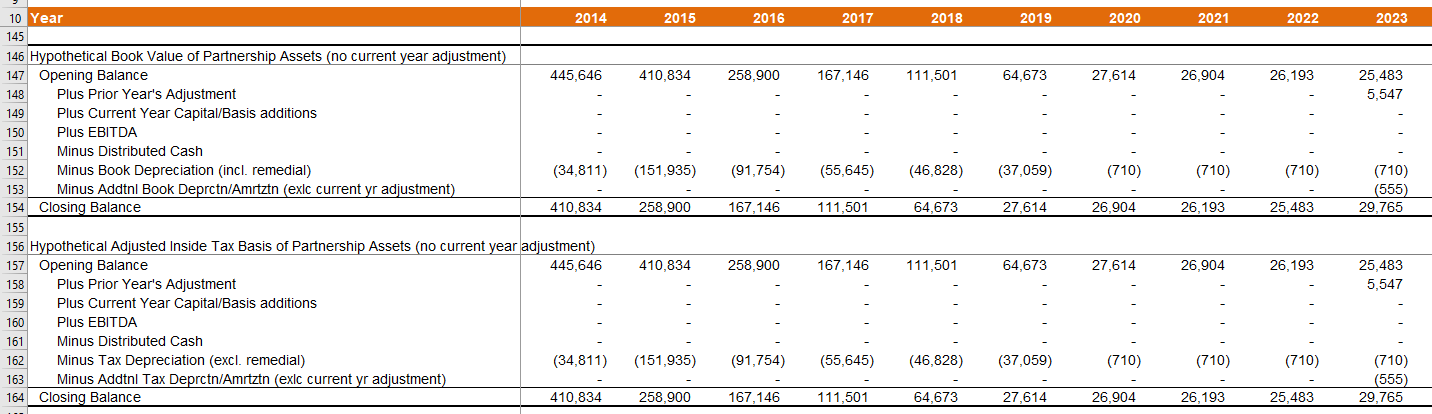

Hypothetical Liquidation at Book Value

This is the risk that when the inside capital account is negative the tax investor may have to repay taxes. A way to layout this amount is shown below. The issue is whether the hypothetical book value should affect the cash flow and the IRR to the tax investor.

Issue: If You Hit a Capital Constraint (Where the Capital Falls Below Zero), How Exactly Will This Affect The Tax Equity Investor

Proceeds in liquidation must be distributed according to the positive capital account balances of the partners;

Partners with deficit balances in their capital accounts upon liquidation are unconditionally required to restore such deficit balance to the partnership.

Relatively meaningless item: Partners’ capital accounts are maintained in accordance with the rules found in the Regulations (i.e., the allocation is reflected in the partners’ capital accounts for book purposes);

provisions to avoid the partner having a negative adjusted capital account

The partnership cannot allocate losses to cause the partner’s capital account to be lower than what the partner is actually or deemed obligated to repay (an Adjusted Capital Account deficit);

Definitions

Issue: What Happens When Inside Or Outside Capital Accounts Fall Below Zero

What is the Business With PAYGO

When a partnership is dissolved, its assets are either sold or written off. Any gain or loss on the sale (sale price less basis) is allocated to the partners in accordance with the liquidation/dissolution section of the partnership agreement and remaining cash is then distributed. In order to comply with the capital account maintenance rules, the cash must be distributed in accordance with each partner’s positive capital account balance.

The allocation rules spelled out in the liquidation/dissolution section of the partnership agreement are integral to Hypothetical Liquidation Book Value (HLBV) accounting used in most renewable energy deals (See Hypothetical Liquidation Book Value section)

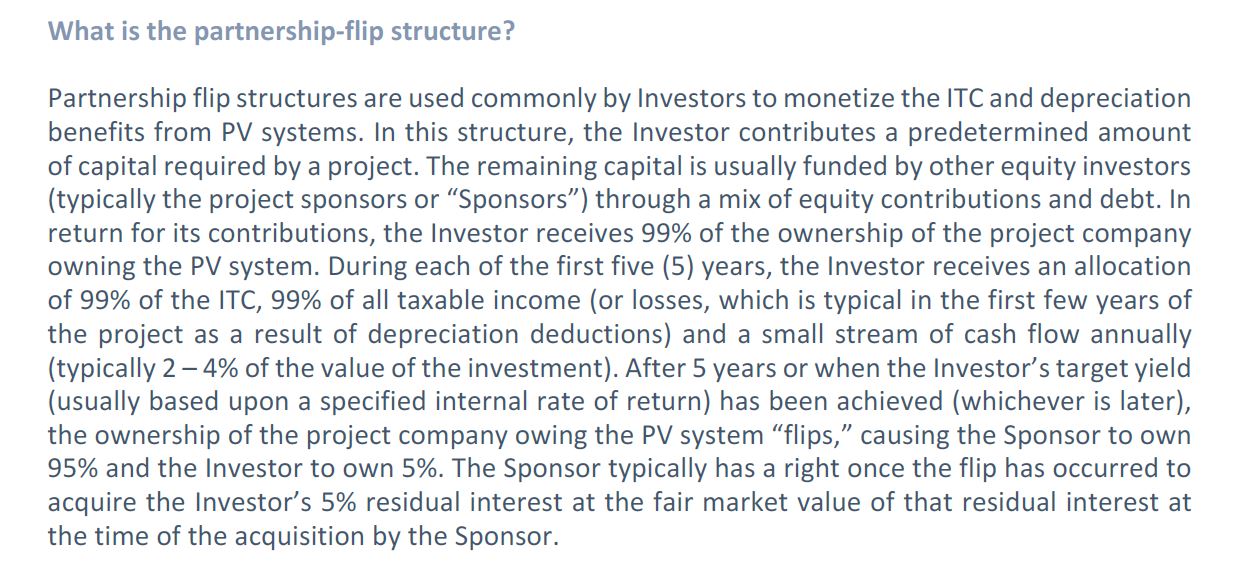

Transaction with ITC instead of PTC

• Tax equity funds 1.3x ITC amount

• Tax Investor priority cash distributions based on % of investment – 2.0% pre-flip, 4.3% post-flip

• Tax Investor common cash allocations – 0.0% pre-flip, 5.0% post-flip

• Tax Investor taxable income allocations – 99% pre-flip, 5.0% post-flip